DNS the easy parts

DNS

The Internet’s success is predicated on the Domain Name System or DNS. We’ve all heard of it, many of us loosely understand it but, like all things, when you need to fix it knowledge gaps become painfully obvious.

When it comes to diagnosing network issues, understanding adblocking, speeding up queries or protecting privacy, you can bet DNS will be mentioned. Unlike other protocols such as Network Address Translation , or Open Shortest Path First, DNS is a network fundamental that every engineer should have down. Sadly, during my CCNA studies, it did not get much more than the cursory explanation.

Overview

DNS is a protocol that can map IP addresses to human readable names. When a user types example.com into their browser bar and hits enter, the machine does not know how to reach example.com without first translating it into an IP routable address.

Before any network activity takes place between the client and the destination, a DNS lookup must first be conducted. Luckily, DNS is fast but it does add latency to the request. If this transaction fails the client will be unable to make a connection to the server. A user could, alternatively manually enter the servers IP address and this would work - as long as the server is up. But if we could remember IP addresses as readily as we do names, DNS would be redundant.

It is worth noting that DNS also allows us to clump many IP addresses under one namespace. For instance, we can reach hosts on our local network using domain names instead of IP addresses. We use DNS for more than just browsing the web; emails, IoT devices and many other services that make networks invisible to the majority of users are powered by this system.

From ten thousand feet, lets examine how a simple name to IP address translation takes place.

DNS Resolution

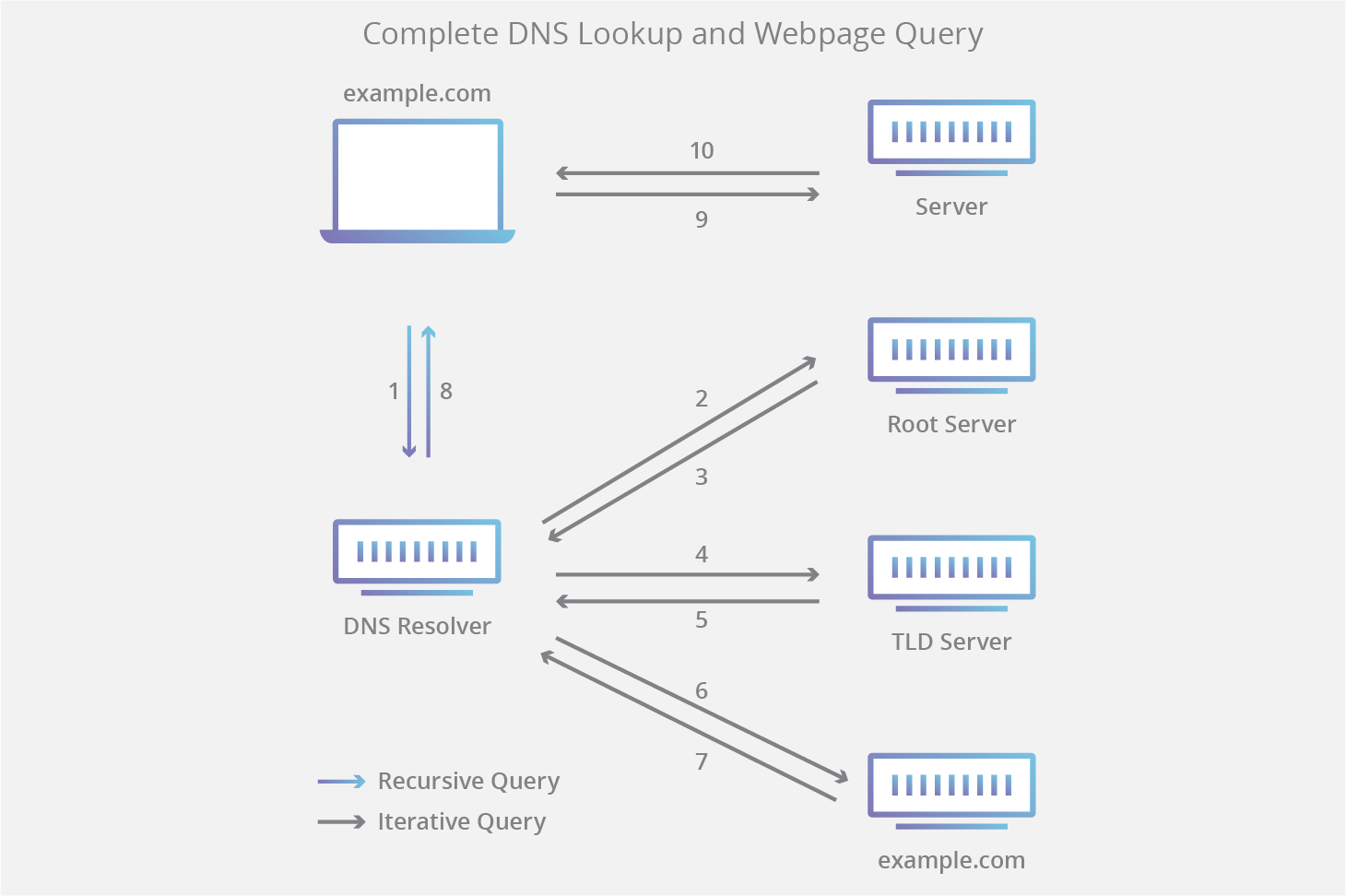

In the below diagram we have a series queries starting with the browser asking for the address to example.com and ending with the server delivering content back to the browser.

Figure 1. Simple DNS Lookup - attrib

Figure 1. Simple DNS Lookup - attrib

When our above client types example.com into the browser and hits enter, a series of steps are taken by the client and external servers to translate the human readable name into a machine readable IP address.

Each step broken down:

- After the user hits enter, the browser will check to see if the address has been cached, if not the operating systems cache will queried, and if both fail, the system will send out a request to a DNS resolver.

- Our resolver will parse its own cache and if nothing matches, will then forward a request to one of the DNS root name servers. Root name servers are at the top of the DNS hierarchy and are represented by the right most

.of our websites name. - Once received, the root name server will check its zone file for the Top-Level Domain (TLD) matching the request - in this case

com. It returns the address ofcom’s name server back to our resolver. - Our resolver now forwards a new request, this time to the

comTLD authoritative name server. - The

comname server checks its zone file for the subdomainexampleand returns that address to the resolver. - Now our resolver can ask the DNS server responsible (authoritative) for the

exampledomains address. - The server responds with the address to

example.com. - Our resolver, having sent out three requests up to this point, will now forward the correct IP address to the client. It will also save the address in its cache for future lookups.

- The browser will now initiate a connection using

HTTPwithexample.com. example.comhaving received the connection request, begins transferring data to the clients browser.

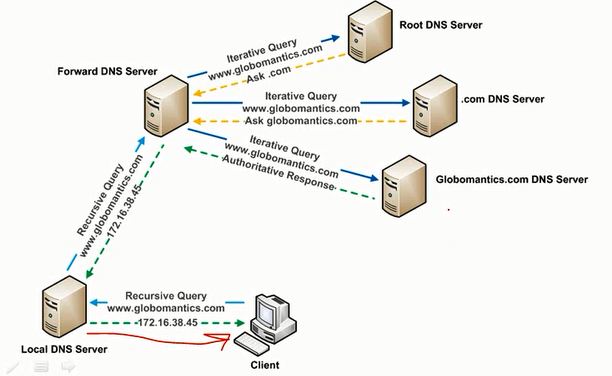

This is a very simplistic resolution. It works well in common household networks where your wireless router is not a DNS server. If you are instituting a firewall or managing your own name server, the below diagram is a more likely reflection of what is happening.

In the above example, the local DNS server sends a query to a recursive resolver from a large DNS provider. As stated in Figure 2, this can also be called a Forward DNS Server. The forward resolver will conduct all the iterative requests on our behalf before returning the answer back to our local DNS server, who forwards it to the client.

Why Root?

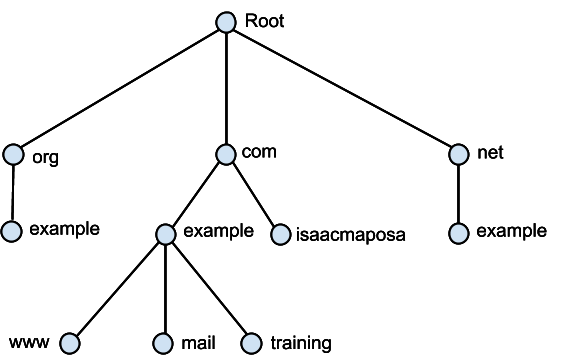

DNS works in a hierarchical structure with the root or . being at the top of the tree - very similar to the Linux file structure.

So why does the recursive resolver go straight to the root name server, and not say the com domain?

Looking at the above example we can see that everything is connected to root. So, the resolver must start with the only known address it has; root. Logically, it is the only server that can reach all possible domains.

Top-Level Domains

After querying the root server, it will return the TLD name server for the domain being queried. The TLD server contains all the information for domains that share a common extension, such as edu, com, or whatever comes directly after the last dot in the url. More simply, the name server for net will have the address for every website that ends with net.

So, when the user requests example.com, the TLD name server of the com domain will reply with the address of the authoritative server for the example domain. Simply put, the name server who looks after the com domain knows where to find every single domain that uses a .com and will return the websites address back to the resolver, completing the lookup.

Top-level domains can be broken into two groups:

- Generic (gTLD):

- Addresses such as

com,net, andgov.

- Addresses such as

- Country code (ccTLD):

- Country specific,

jp,au,ca.

- Country specific,

With an address such as example.com.au the resolver will still query the root name servers but it will send the resolver to the country specific top level domain of au. The domain to the right of the last . will always be queried first.

We can demonstrate this by running drill bbc.co.uk -T or dig bbc.co.uk +trace.

Subdomains

Technically, after the TLD, each domain down the tree can be referenced as a subdomain; example in example.com being a subdomain of the com TLD.

Typically, subdomains more often refer to addresses such as api.github.com with api being a subdomain of github.

You can see the resolution by running drill m.facebook.com -T or dig m.facebook.com +trace.

At the date of publication, the facebook lookup provided a good example of subdomain and CNAME resolution. I have included a truncated output below.

>> drill m.facebook.com -T

...snip...

. 518400 IN NS l.root-servers.net.

. 518400 IN NS i.root-servers.net.

com. 172800 IN NS l.gtld-servers.net.

...snip...

com. 172800 IN NS m.gtld-servers.net.

facebook.com. 172800 IN NS a.ns.facebook.com.

facebook.com. 172800 IN NS b.ns.facebook.com.

m.facebook.com. 3600 IN CNAME star-mini.c10r.facebook.com.

c10r.facebook.com. 3600 IN NS a.ns.c10r.facebook.com.

c10r.facebook.com. 3600 IN NS b.ns.c10r.facebook.com.

star-mini.c10r.facebook.com. 60 IN A 157.240.8.35

Terms

Essentially all technical efforts wallow in acronyms and special “terms of art” […] with several non-obvious terms to confuse those who have not been involved for a while.

- RFC 4144 - How to Gain Prominence and Influence in Standards Organizations

Sums up many of the terms used to express components of the domain name system. A brief description of the main offenders follows and how to examine them using drill. If drill is unfamiliar to you, dig will work just the same. nslookup is not covered in this post, but will essentially do the same thing.

DNS resolver

The ‘resolver’ is the agent between the client and the name servers. A resolver will start the queries that eventually return a valid address translation for the client.

A recursive resolver knows how to traverse the tree to deliver a response to a query.

Authoritative Server

Owns the domain, or has all the records for that domain. E.g. the com name server, knows the whereabouts of every single domain that uses it. Popular sites such as google.com, yahoo.com and github.com are all domains under the com authoritative server, it knows the address to each of those sites DNS server within their network.

Top-level Domain (TLD)

Domains that are one level below the root are known as top level domains.

- Examples:

com,jp,edu

Country Code TLD’s such as au, uk and nz are examples. taste.com.au will be resolved in the following order:

.- Root- ->

.au - ->

com.au - ->

taste.com.au

This can be seen via drill -T taste.com.au which will trace (what -T does) through each root name server all the way to the A record of taste.com.au.

Recursive request

When the client needs to get the address of a URL, it first checks its cache and if not found will send a request to its recursive resolver asking for the address. Often, the resolver being queried will be your ISP’s default name server (please don’t do this; they monetize it), or something like Google’s public DNS server; 8.8.8.8. My opinion: use 1.1.1.1 or some other provider - Google are using you, too.

The recursive resolver will then begin a series of iterative requests on your behalf.

For the most part recursive queries begin with the client and end at the recursive resolver in a kind of A->B, B->A relationship. This is because the resolver is doing iterative queries on your behalf and here lies the big difference between recursive and iterative requests.

Recursive queries require an answer

As Microsoft puts it:

recursive query indicates that the client wants a definitive answer to its query. The response to the recursive query must be a valid address or a message indicating that the address cannot be found.

Meaning a recursive can only reply with either the address, or an error (NXDOMAIN) but not a referral to another name server.

Iterative request

Generally, the queries from a recursive resolver to other name servers are iterative. They leave the resolver and start at the top of the DNS tree via the root name servers. The root replies with the appropriate domains name server. The resolver then makes another query to that server. The iterations continue down the hierarchy until an address is resolved.

Unlike recursive queries, iterative requests will accept any answer; address, error or a referral to someone who knows more.

Microsoft again:

An iterative query indicates that the server will accept a referral to another server in place of a definitive answer to the query.

Non-Iterative request

When a query is made and the resolver has the address mapping in its cache, it will refer the client immediately to it. No further queries are made and this is known as a non-iterative request.

Record Types

A:

- IPv4 address associated to domain name.

- Running

drill example.comdefaults to returning an A record.

AAAA:

- IPv6 address association.

drill aaaa example.comwill explicitly return the IPv6 address, if it has one.

Mail Exchanger (MX):

- Mail exchanger records containing the emails associated to the domain.

drill mx google.comwill return all the mail exchangers, and each ones priority.

Name Server (NS):

- A list of name servers connected to the domain.

drill ns cloudflare.comoutputs their name server domains.

Pointer (PTR):

- Pointer file for reverse DNS lookups

- For example, do the following:

drill defence.gov.au. Take the IP address -203.6.74.5and do a reverse lookup using only the IP address.drill -x 203.6.74.5. It should returnwww.defence.gov.au. - When both the forward (name-to-address) and reverse (address-to-name) entries match, this is known as a forward-confirmed reverse DNS. Its a weak form of authentication - it proves the IP and domain are owned by the same entity. Sender Policy Framework and MX records are often better indicators of authenticity. Nonetheless, it can be a method used to whitelist a domain, or a reason for other mail exchangers to blacklist, or drop mail to that domain, if the lookup fails.

Canonical Name (CNAME):

- Can be used to alias one name to another, most often to an A record. It operates a bit like a treasure map with clues pointing to the treasure - the A record.

drill blog.cloudflare.comreturnsCNAME cloudflare.ghost.iowhich directs to theArecord.

As a example of how to read a zone file, or response with CNAME information:

NAME TYPE VALUE

--------------------------------------------------

bar.example.com. CNAME foo.example.com.

foo.example.com. A 192.0.2.23

This should be interpreted as:

bar.example.com.is an alias for the CNAMEfoo.example.com.. A client request forbar.example.com.will be returnedfoo.example.com.

The next query to the example domain will be asking for the foo subdomain. Which will be returned an A record with address 192.0.2.23.

This adds latency as another round trip must be conducted and generally chaining CNAME’s is considered bad form.

Text record (TXT):

- Contains extra data such a sender policy framework and encryption information.

- Often contain valuable information about the domain, for instance:

>> drill telstra.com.au txt

;; ANSWER SECTION:

telstra.com.au. 1303 IN TXT "v=spf1 include:_spf.telstra.com.au ~all"

telstra.com.au. 1303 IN TXT "google-site-verification=GeZnWLAmVtLSHbjW5VEawrbtjQzhSY-e4wsT9VBaJkU"

telstra.com.au. 1303 IN TXT "7EC66119-3393-46B7-9DA9-9AD7643925FA"

The TXT returned some information about the telstra.com.au domain; they use Google Apps in their systems.

A better one is vodafone.com.au who I know for certain use Salesforce (I saw it on their systems in store recently) and that is readily confirmed in their TXT response.

>>> drill vodafone.com.au txt -t

;; ANSWER SECTION:

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "MS=ms76000886"

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "407D-EB23-4E8F-A96D-CA1D-27F0-1FD5-B8DC"

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "google-site-verification=s_5FhJrgc0EtEXFv6eikEih2i1fjH18PIz2e93qxOLE"

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "NrkgBWZQJfU+vkg4E7z1RchofBb+WL+Ab0NdlXM6OZ4lo5KJLtj7U8LVEV+iASwT/7Zrn4OqBQ5ETPOrPn9cwA=="

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "v=spf1 ip4:54.171.206.163 ip4:101.119.57.42 ip4:119.11.1.42 ip4:101.119.57.43 ip4:119.11.1.43 ip4:101.119.57.14 ip4:119.11.1.14 ip4:216.9.247.4 ip4:216.9.247.48 ip4:216.9.247.49 ip4:216.9.247.68" " include:_spf.salesforce.com include:herald.responsetek.com include:srs.bis3.ap.blackberry.com include:taleo.net include:production.fxdms.net a:mail1.hutchison.com.au a:mail2.hutchison.com.au a:mail3.hutchison.com.au a:mail4.hutchison.com.au ~all"

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "BR6ST3VIM"

vodafone.com.au. 506 IN TXT "MS=ms13634633"

The -t flag indicated the response needed TCP as the message size was too large to fit in one UDP packet.

drill lets you know:

;; WARNING: The answer packet was truncated; you might want to

;; query again with TCP (-t argument), or EDNS0 (-b for buffer size)

Start of Authority (SOA):

- Contains administrative info about a zone such as domain owner, contact details and serial number.

- Serial number is used to determine the currency of the zone’s data.

drill SOA taste.com.au

>>> ;; QUESTION SECTION:

>>> ;; taste.com.au. IN SOA

>>>

>>> ;; ANSWER SECTION:

>>> taste.com.au. 176 IN SOA dns0.news.com.au. hostmaster.news.com.au. 2019060600 900 600 604800 300

Each tabbed section in detail:

INandSOA; Internet and Start of Authority.dns0.news.com.auis the primary name server.- The email contact for the domain;

hostmaster.news.com.auis equal tohostmaster@news.com.au. The first.should be replaced by an@symbol. 2019060600is the current serial number for the domain. Serial numbers are used by other DNS servers to check its trustworthiness in delivering up to date information.900The time in seconds the secondary name server should wait before checking the master’s SOA record for changes. Also known as therefreshrate. More aptly this means; how long am I willing to accept my secondary server having out-of-date information.600is theretrytime it should wait before trying anotherrefreshif the last one failed.604800is theexpirecounter in seconds. It lets the secondary name server know how long to hold their information before it is no longer considered authoritative. Generally, this is a large number, and should always be greater thanrefreshandretrycounters.300is theminimumtime-to-live in seconds before the records in the zone are considered invalid.

Today, the refresh, retry, expire and minimum are still important but used much less frequently. RFC’s 1996 and 2136 have included the NOTIFY and UPDATE opcodes to allow the master DNS server to send updates to its slaves, rather than waiting for them to poll the master for changes.

Wrapping Up

The domain name system is far too technically rich to even scratch the surface in one short post, but hopefully it helps to cover off a few confusing points. If nothing else, it may serve as a launch pad for some to go out and read more on this incredible and interesting protocol. One which we use hundreds of times a day.

If you want to use a state of the art DNS service that respects privacy, is customisable, easy to use and secure then check out NextDNS. It’s free to sign up, can be configured on routers, browsers and devices. My android devices all override their system DNS and block ads so effectively it feels like internet is free of them! If you’re interested, try it here at my affliate link.

Keep up to date with my stuff

Subscribe to get new posts and retrospectives