learn docker in one month

Learning Docker in one month

Yep, one month.

Docker basics

What

docker is a product that uses operating system virtualisation to created packages and applications which live within a “container”. These containers bundle together applications and dependancies without the need for installation on the host operating system. Containerisation is meant to empower developers by providing a “written once and run anywhere” methodology.

Why

Some of the core reasons to use docker.

- The ability to have standalone applications and packages with dependencies that are isolated for the base operating system and other applications is a boon for developers and users,

- Linux hosts can have several docker containers running without fear of contaminated package versions or dependancies causing errors,

- Sharing consistent environments between developers is possible as each docker container image is idempotent, meaning the result of building a docker image will be the same whether built once, or one thousand times,

- Version pinning is possible making compatibility issues on new release cycles less problematic, and testing of packages easier to implement,

- Continious Integration is a perfectly paired with docker allowing each new release, or push to the repository to be built automatically with a new docker image, and tested to ensure against regression.

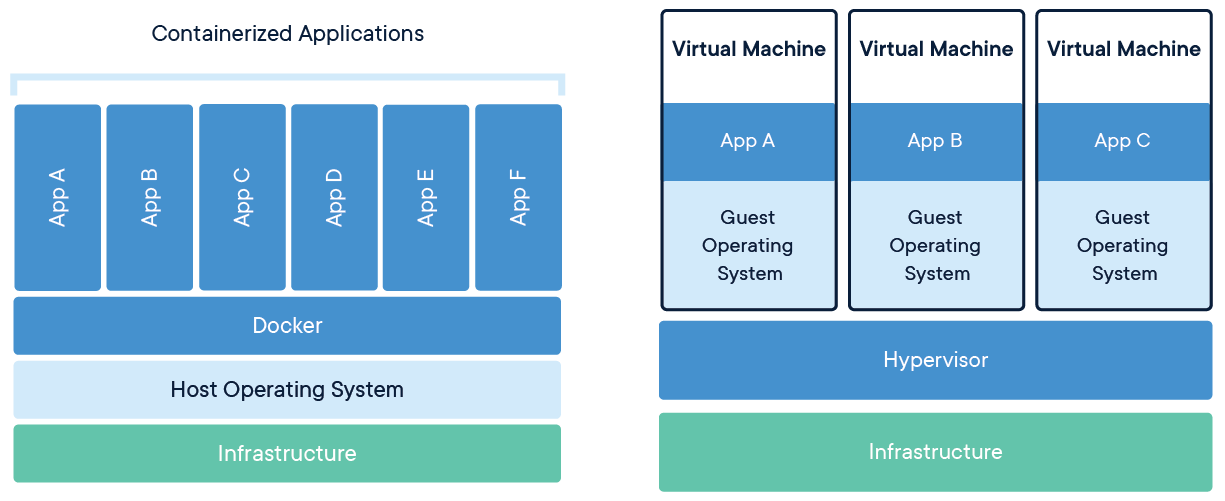

Virtual Machines aren’t docker

Docker and virtual machines differ in their implementation and uses cases. They are complimentary rather than competitors and service different needs through each use-case.

Containers leverage the base operating systems kernel whereas virtual machines initialise each machine with its own hardware virtualised operating system. Although docker utilises the host’s operating system, its application are seperated from the kernel ensuring isolation via the docker engine.

Regardless, each technology should be utilised as a method to achieve an outcome rather than be a dogmatic position for any one developer to live and die by. In fact, both methods can be used in conjunction, it is possible to run docker contianers within virtual machines - this being something I do often in Vagrant.

Docker processes

An important distinction with docker is its process orientation. Containers are designed to execute one process and then quit - the length of the running process arbitary but once its is complete the container will effectively exit.

this is an important point for new docker users. It contrasts heavily from a virtual machine which will live forever, sitting idly doing nothing until instructed.

For example, a contianer may run a command line application that fetches the weather from your local area. Once the container has finished this process it will stop and cease to draw any resources until manually called again by the user or application.

How does docker work

docker container run -d -p 8080:80 --name myapache httpd

There is two main concepts to grasp with docker; images and containers.

images

Images can be thought of as virtual machine snapshots - a point in time that contains an application, its dependancies and files. Unlike a virtual machine this “snapshot”, or image is immutable and static. It serves as a blueprint, rather than a dormant virtual appliance waiting to be brought back to life.

To sum, images are what we then create containers from and ensure that each launched container will be identical to the base image.

containers

Containers are the running applications brought to life from a docker image. This is the process which does some work, be it short or long lived. At their essence, containers are meant to be disposable, existing only to complete their task and then exiting.

Principles of containers:

- Immutable

- Disposable

- One process per container

Demo #1

Let’s start a docker application.

docker run --rm danielmichaels/http-tracer http://nyti.ms/1QETHgV

You should see something similar to the following:

Unable to find image 'danielmichaels/http-tracer:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from danielmichaels/http-tracer

c87736221ed0: Already exists

9dc197b2c846: Already exists

02f2755d81e6: Already exists

012e932ae3a4: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:b463068aec6a475854277d8e0a485281166d1fa18eb7c9c8e09cb858e3031684

Status: Downloaded newer image for danielmichaels/http-tracer:latest

Docker always checks the local machine for any images matching the request. If it does not find any it will check its upstream repository for any matches, in this case, Docker Hub.

If found, docker will then start to pull down the container’s image. Once its finished downloading, docker executes the docker run command. Try it out.

In this example, we’ve downloaded a script that executes once - printing information to the terminal and then exits. The next time the container is called, it finds the cached image and spins up the container much faster. The only slow down being the scripts IO bound process.

Let’s look at a long lived process, such as a webserver.

Demo #2

docker run --rm -it -p 8081:80 nginx

Again, an image will be downloaded (don’t worry we’ll go over deleting images) before it finally runs the container.

This time, nothing should happen and it may appear to have hung. In a browser, navigate to localhost:8081 and observe the terminal where the container is running. Requests will be printed to the screen.

If you are wondering about the -p flag, it is shorthand for --publish and is the mechanism for mapping the host and container port. The host port is first, container second or -p <host>:<container>. For nginx, it expects port 80 so we set the container to that however the host port could be set to any realistic port.

So we should have the nginx default page in the browser, and the request for that page in our terminal. This is a good example of how docker processes can be long running - the webserver is a process and it’s still running.

We can also make this process run without printing anything to the screen by omitting the -it and replacing it with -d or --detach. The terminal should output a long alphanumeric string indicating its container id. Confirm this with docker ps.

To stop detached containers use docker stop <container id|container name>. Again, the id or name used to kill the process should be echoed to the terminal. A docker ps will confirm this.

Lastly, the --rm flag simply removes the non-dead container from the host filesystem. For our purposes, we do not need or want to keep copies of our containers on the system. Generally, its a good idea to keep them for debugging but can really start to absorb a lot of disk space on the host during testing.

To check for this run docker ps -a which will print out any old containers that can be cleaned up. To clean away these container use the prune command: docker container prune.

Bind Mounts

So far the utility has lacked any real substance. I’ve got a web app, how does my code get on here?

There are two methods to mount data to contianers; using --volume/-v or --mount. Docker recommends using the --mount method for a few reasons, namely the ability to share mounts between contianers.

Using -v

Short running container

docker run \ # run docker

--rm \ # remove container once done

-it \ # interactive mode

-v $(pwd):/src python:3 \ # volume to mount with container

python hello.py # process to run; python and script located in the volume - /src

Long running container

docker run \ # run docker

--rm \ # remove container once done

-it \ # interactive mode

# replace -it with -d to detach and run in background

-v $(pwd):/usr/share/nginx/html \ # volume to mount with container

-p 8080:80 \ # port host:container

nginx:latest \ # image to run with tag (latest version)

bind routes -v put area on local to area on container. docker run -d -p 8080:80 --name nginx-bind -v $(pwd):/var/share/html nginx

and --mount

This method is more verbose than -v but much more powerful. Because we are using key:value pairs the order is not important.

From the documentation:

- The

typeof the mount, which can bebind,volume, ortmpfs. This topic discusses bind mounts, so the type is alwaysbind.- The

sourceof the mount. For bind mounts, this is the path to the file or directory on the Docker daemon host. May be specified assourceorsrc.- The

destinationtakes as its value the path where the file or directory is mounted in the container. May be specified asdestination,dst, ortarget.- The

readonlyoption, if present, causes the bind mount to be mounted into the container as read-only.- The

bind-propagationoption, if present, changes the bind propagation. May be one ofrprivate,private,rshared,shared,rslave,slave.- The

consistencyoption, if present, may be one ofconsistent,delegated, orcached. This setting only applies to Docker Desktop for Mac, and is ignored on all other platforms.

To illustrate we are creating our volume (a bind mount) in our current working directory. Inside the directory we have a python script which runs print('--mount!') and nothing more. The file is called mount.py. The structure should look like this:

# tree .

.

└── mount.py

0 directories, 1 file

To mount this file and make it executable via docker we use the --mount option.

docker run --rm --mount source="$(pwd)"/,destination=/apps,type=bind python python /apps/mount.py

Breaking down the --mount starting with source. This is the location of the data to be “loaded” into the container, most often from a local machine. The unix command $(pwd) returns an absolute path, which mount requires—it cannot accept relative paths.

This effectively tells docker to put anything within that directory into a volume and attach itot the container.

Next is destination which can also be called as target. This tells docker to place the source data inside this location within the container. So if I was to set destination=/shazwazza, then the data would be located in the / as /shazawazza.

Lastly, in this example we are setting type=bind. This is the most simple method, though less extensible than volume mounting. For small independant applications it is often best to at least start with a bind type and then when ready move onto volume. See here for detailed information regarding the volume mounting, and when you should use it.

Useful docker commands

docker info

- Displays system-wide information

docker inspect <image/contianer>

- Return low-level information about a container or image

docker container ls

- Returns currently running containers

docker ps

- Shorthand for

docker container ls. Appending-awill show containers that have exited.

docker image ls

- Prints all images on the local machine that have been pulled down from docker hub.

docker pull

- Will download a docker image onto the local machine

docker run

- Runs a docker container, and if not found on the local machine will attempt to download it.

docker flags

--rm: remove container from list once process exitsprune: remove any old or “dangling” images, containers or networks. Good for deleting old cached builds no longer in use. E.g.docker container prune- exec:

docker exec -it myapache bashexecutes the bash shell for an interactive session.

Dockerfile

So far, we have only pulled and ran docker images, or added a mount to a local container. That is useful but dockers biggest selling point is being able to create and bundle our own applications into a container and allowing others to use them on other systems. To do this, we use a Dockerfile.

From Docker:

Docker can build images automatically by reading the instructions from a Dockerfile. A Dockerfile is a text document that contains all the commands a user could call on the command line to assemble an image. Using docker build users can create an automated build that executes several command-line instructions in succession.

When creating a docker image, we most often want to pull from an existing image within a registry such as Docker hub and extend it.

Example

# simple example

FROM jfloff/alpine-python:3.6-slim

ENV LC_ALL=C.UTF-8

ENV LANG=C.UTF-8

RUN pip install http-tracer

ENTRYPOINT ["http-tracer"]

CMD ["pfsense.org"]

The above Dockerfile, has some keyword’s denoted by capitals, followed by an argument. This is the general structure of a Dockerfile and the layout is very important as we will see below. There are many more keywords but that’s reserved for your own experimentation.

All dockerfile’s start with FROM - which basically means “pull this image and extend it with the following..”

In this particular application, we need to ensure the languages are set correctly. Dockerfile’s allow users to set Environment Variables with the ENV keyword.

Perhaps the most important and well known command is RUN which tells docker to call the following commands within the container. In this case, as we are building atop of an alpine-linux minimal python version, pip comes bundled with it. If the image was ubuntu based we could call apt-get and so on.

The next two lines (layers) are special to this commandline application. ENTRYPOINT defines the command we want to execute within the container and because our app, http-tracer is installed in the PATH as apart of its pip installation, it is executable. Typically, ENTRYPOINT is used in contianers that are designed to be run as an executable, which this application is.

CMD is similar to ENTRYPOINT except we can only use it once and it is used to set default commands or parameters. the argument that follows a CMD keyword will run anytime the container is executed without specifying any arguments with it. So in this case, out http-tracer container will be executed with "pfense.org" as its default argument. If the container runs with a command, this default will be overwritten.

More simply, to allow user input;

The ENTRYPOINT specifies a command that will always be executed when the container starts. The CMD specifies arguments that will be fed to the ENTRYPOINT

confused?

Calling our docker image without any arguments will result in the following:

Whereas if we set a argument of “cisco.com” it will overwrite the default and return data relating to that parameter.

Another example worth looking at is the ping command. You can execute that with a dockerfile containing the following:

FROM debian:wheezy

ENTRYPOINT ["/bin/ping"] # executes when container is run

CMD ["localhost"] # executes unless user input supplied

layers

In a Dockerfile, each line is a layer.

-

layers cannot shrink the size of the image

-

layers are cached (checks the Dockerfile lines for differences)

-

caching means it does not need to be rebuilt, only new layers

-

container is a layer, one that exists only while the container lives:

- the build layers are read only - cannot edit them and are shared across many containers

- if the image needs updating, all layers must be rebuilt

-

container layer:

- read write

- modifications of source, or volumes within the container exist only within that container unless rebuilt into a new image

-

image layer:

- read only

docker networks

Docker also provides a networking layer, allowing many contianers to be on a local area network. If this is not setup, each container is essentially within its own virtual LAN and cannot communicate with other containers. This is a big topic so read up on the docs [here].

The basics are as follows:

- to create a network for a

mysqldatabase andnodeapplication to communitcate run:docker network create <name> - see that your network has been created with

docker network ls - inspect your network with

docker network inspect <name>

To add containers to a network, and test they have connectivity with ping is just a matter of adding them to the network with --net.

# create mysql on docker network named 'test'

docker run --rm -d --net test --name test_mysql -e MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD='root' mysql:5.6

# create node linking to the 'test' network and spawn a shell

docker run --rm -it --net test --name test_node node:8 /bin/bash

# once they've been built it will drop into a shell

# test the network connection by trying to ping test_mysql

ping test_mysql # from node /bin/bash shell

# unless explicitly denied, this gives access to internet

ping 1.1.1.1

Docker enough to get by

That is really enough docker to start playing around and learning to be comfortable in it. This hasn’t covered docker-compose which is another powerful tool, but having a baseline understanding of docker is paramount. The whole point is to learn slower than you think, and be exposed to new technologies over a longer period of time - rather than glossing of all the new shinies and not really learning anything. It’s okay to be slow - its all time under tension and repeated small exposures that eventualy lead to true understanding.

Keep up to date with my stuff

Subscribe to get new posts and retrospectives